Clifford Carver was born July 16, 1924 in Stony Point, Manitoba to William and Maggie Carver and grew up in a Métis family. He spent his early life in the St. Clements area and eventually met Florence Smith, from Belair, Manitoba. Together they had several kids and settled for a time in Beaconia in the 1950s.

By the early 1960s the Carver family totalled 12, with 10 children, and the couple moved to Winnipeg in a terrace at 27 McGregor Street after spending a short period in East St. Paul. However, within the first little while of being in the block, a pipe burst and fire broke out in the building which left the large family without a place to live.

The family eventually found another home to live, which was a terrace just one street over at 39 Andrews Street. The Carver parents’ lives were extremely busy with 10 kids, but adding to it was the fact that one of their sons Dennis suffered from chronic pneumonia. He spent the vast majority of his first three years of life at the hospital getting care.

During this time, the family struggled financially. In 1961, the family was referred to the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) by the Children’s Hospital. Within a few more years, they had a family of 15. Clifford was only able to find part-time work as a labourer and in a coal yard because of a lack of education. Meanwhile, Florence struggled with depression and alcohol use, potentially exacerbated by her hysterectomy surgery she received after their youngest was born. The two received around $230 per month in welfare.

The Carvers’ home on the right, 39 Andrews Street (January 15, 1965), Winnipeg Tribune.

The two relied on routine visits from East St. Paul councillor Donald Deans, who began seeing them in 1961 and brought them food vouchers. The Carvers originally lived in East St. Paul and because of existing legislation, they kept receiving welfare from the RM of East St. Paul instead of Winnipeg after they moved to the North End. Beginning in late 1963, they were also helped by the parish guild of St. Bartholomew’s Anglican Church with donations of food, clothing, and appliances.

All seemed to be going well in early 1964, but later on in the year the family’s living conditions regressed. Though the parents both struggled with various issues, both Deans and the president of the guild Veronica Mensforth agreed that they were trying, deserving of help, and that their kids were happy.

On Christmas Day, Florence walked out on Clifford and the children so Clifford asked her mother to help look after them, including their baby boy who was sick. She stayed for two or three days. Florence eventually returned a couple of days later, however she only stayed a few more hours before leaving again. On New Year’s Eve of 1964, Clifford left home in the late morning to find Florence and put their oldest son, who was 15, in charge of the children when they were out.

Six of the Carver kids and their babysitter (January 8, 1965), Winnipeg Tribune

A few hours later, after the newborn was treated by home-care for his lung condition by the Victorian Order of Nurses, the Winnipeg Police were informed that neither of the parents were home and called CAS. Both a social worker and councillor Deans arrived and found little food in the house. The social worker took the two eldest boys to the store and bought $20 of groceries and instructed the police to periodically check in on the children. The infant who was sick was brought to the children’s hospital.

Meanwhile, Clifford found his wife at a The National Hotel on Main Street near Logan Avenue drinking and decided to join her and her mother while persuading her to return home. The police called CAS again when the 15 year-old decided to leave home and they were informed that the parents were likely at a hotel drinking. Clifford returned home around 10:30 and was not drunk. Florence returned soon after.

The police warned them to stop leaving their children alone and to address the dirty state of the house. A few days later, the police returned and found the house in the same state and brought the case to the Crown prosecutor. On January 7th, charges were filed against the couple for neglect of their youngest son and they were ordered to appear in court the following day.

The couple denied legal representation and put a 17 year-old neighbour in charge of their children when they appeared in court in front of prosecutor John D. Montgomery and judge Isaac Rice. They preemptively pleaded guilty to all charges.

John D. Montgomery (n.d.), J. Gordon Shillingford Inc

The couple’s trial lasted 25 minutes and the vast majority of it was Montgomery explaining his account of the story of the past several weeks at the Carver residence. The rest of the time was spent by Rice lacing into the couple over the charges and demeaning Florence over the number of children she had.

January 22, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

The final part of the trial involved Rice asking how much each of the defendants had to drink on the night of New Year’s Eve, and comparing the cost of the 20 or so beers they each had, bought by Florence’s mother, to the price of milk that could have been bought for the children.

Judge Isaac Rice (December 8, 1966), Don Hunter for the Winnipeg Tribune

The verdict by Rice was unsurprisingly guilty, and he sentenced each of them to one year in jail. His closing monologue was a lamentation about how Montgomery, and especially himself, would be the scapegoats of the people “coming out and crying” for the couple.

January 22, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

The couple was immediately taken to jail and their children began to be scattered all over the city in CAS foster homes in the West End, Fort Rouge, East Kildonan, Elmwood, St. James, and St. Vital.

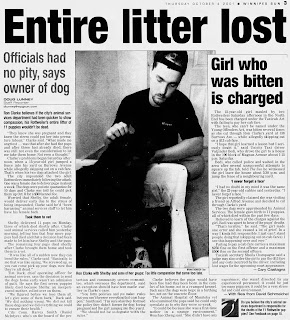

In an astounding display of sensationalism, the Winnipeg Tribune plastered the faces of six of the Carver children on the front page of the paper the day after the verdict in a story rife with inaccuracies about the case and very descriptive imagery to paint a specific picture of the Carver family of living on a “raw fish diet” with parents that went on a “two day drinking spree.”

January 8, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

In response, civil lawyer Harry Walsh voluntarily stepped up to represent the Carvers and within a week had filed both an appeal to overturn the conviction in County Court and an application for bail to have the couple released.

January 16, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

Walsh compiled two dozen different grounds for the appeal: including the couple not understanding the charge and penalty of the plea, them not having an opportunity to consult with counsel and denying a lawyer because they said they could not afford one, that the allegation of the parents being absent from the home for 30 hours and kids not being fed was not factual, and that “the conviction was against law, evidence, and the weight of evidence.” He also challenged the “highly inflammatory address” given by the prosecutor.

Harry Walsh Q.C. (n.d.), Jewish Foundation of Manitoba

In the lead up to the retrial, the Carvers were also arrested on a separate offence that was also reported by the Tribune for being drunk on the street and “several other charges.”

Judge W. A. Molloy in centre (December 12, 1956), Winnipeg Tribune

The case took around three months to re-litigate and it was overheard by Judge William Austin Molloy. At the end of March, Molloy delivered his verdict which acquitted Clifford on all charges and gave Florence a one-year suspended sentence because he felt she was “emotionally disturbed” and “needed sympathy and assistance she couldn’t receive in jail.”

March 30, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

Throughout the process, the Winnipeg Tribune also faced intense criticism for its reporting in the lead up and aftermath of both cases and interference of the trial. But more, the re-trial revealed that almost all of the details initially reported were factually inaccurate.

Clifford had not left the children for 30 hours, he had left them for under 12. The kids were not starving from only having eaten since the previous morning, Clifford had fed them porridge that morning prior to leaving and there was still cold meat, bread, porridge, and powdered milk in the house when he left.

Even the baby, who was taken to the hospital because of an acute respiratory attack on December 31st, had been taken in the previous day by Florence’s mother for a checkup and the doctor found him happy and his lungs to be in good shape.

But even before all the facts came out, CAS found the case how it was prosecuted from the very beginning to be abnormal. CAS Executive Director Asta Eggertson was clear that the organization dealt with over 500 cases per month, and outlined just how heartbreakingly common it was for families to have extremely poor living conditions, yet the only difference with the Carvers was that they went to jail for it.

July 9, 1965, Winnipeg Tribune

After the case, the Carver family returned to their lives out of the public spotlight. Florence passed away at 51 years old on July 19, 1983 and Clifford passed away on July 27, 1990 at 64.

Walsh, who spent the first three months of 1965 successfully defending the Carvers, went on to play a key role in abolishing the death penalty in 1976.

Harry Walsh in his office (n.d), Mike Deal, Winnipeg Free Press

For his career spanning 71 years, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Manitoba in 2003 and the Order of Canada in 2010. At the time of his passing, February 24, 2011, he was Canada’s oldest practicing lawyer at 97 years old.